in consultation with Carolynn Harvey, DVM

Rabbits have a very round-about, complicated way of getting their food digested, and they do not process all foods equally well. For instance, the ability of the post-weaning rabbit’s small intestine to digest fructose (fruit sugar) increases, while the ability to digest all other sugars decreases (Buddington 1990). So, a mature rabbit can easily digest (and get fat on) the sugar in fruit, whereas the sugar in a candy bar can make the same rabbit sick. This is because sugars and starches that the small intestine can’t digest will wind up in the cecum. If they arrive in large quantities in the cecum, they encourage the overgrowth of toxin-producing bacteria with consequent illness to the rabbit.

Adult rabbits absorb protein in the small intestine (up to 90%), but this depends on the source. The protein in soybean meal is very digestible, but a high portion of the protein in alfalfa (which is largely bound to the plant cell wall) is indigestible to rabbits. Rabbits digest cellulose poorly (Fraga 1990). This seems a paradox for an animal that lives naturally on vegetation. But this is part of the plan. The low digestibility of fiber and rapid elimination of large, hard-to-digest particles enable the rabbit to “maintain a higher level of feed intake than it would otherwise be able to.” (Sakaguchi 1992)

Particle Sizes and Transit Times

Indigestible fiber is indigestible whether it’s pulled off the bark of a tree or blended into a feed, yet the size and type of the fiber can affect the length of time it takes to pass through the GI (gastrointestinal) tract.

Contrary to what you might expect, the large particles don’t get stuck inside the rabbit, while the small ones exit easily. It’s the other way around.

Transit times of particles moving through the GI tract have been measured, in several scientific studies, by placing markers in the feed. High-fiber alfalfa meal, pelleted into large particles (up to 3mm), moved through the digestive system in 14.1 hours in one study. When same high-fiber feed was ground to a finer size (1mm), it took 15.9 hours to pass through the digestive tract.

Markers in a pelleted low-fiber high-starch feed passed in 20.1 hours (Gidenne 1992). Why are smaller fibers and high-starch feeds slower in getting through? Because small particles and excess starch are sent to the cecum for fermentation, which takes extra time. Fluids and small particles are separated in the colon and moved backward into the cecum (Cheeke 1987), while large particles are passed quickly through the colon.

One study used particles up to 5mm in marked feed, which passed in 5 hours (Sakaguchi 1992). This may closely approximate the size of chewed hay. I can say with strong certainty–from caring for disabled, diapered rabbits on a monitored diet with strictly scheduled feeding times–that the oat hay I give my rabbits in the morning is passed by the afternoon (4-5 hours).

Fast and Slow

So which is more desirable, fast moving or slow moving particles? Some of both are needed: a sizable quantity of coarse indigestible organic material to keep the gut working at an optimum rate and enough (but not too much) digestible material to be absorbed in the small intestine and cecum.

How do you know when there is optimum movement? Try listening. You should hear normal “gut sounds” caused by the fluid ingesta mixing with gas as it moves along. Too much noise may indicate an irritated intestine, while no sound at all indicates stasis.

What Is a Balanced Diet?

A balanced diet for a rabbit is a nutritional and a time balance. It includes protein, starch, carbohydrate, vitamins, and minerals in slower moving digestible material that can be absorbed. It also includes large amounts of fast-moving indigestible organic material. The next thing to learn is specific quantities of digestible and indigestible material that are appropriate for your rabbit. *

literature cited

Buddington, R. and J. Diamond. 1990. Ontogenetic development of monosaccharide and amino acid transporters in rabbit intestine. American Journal of Physiology 259:G544-55.

Cheeke, P.R. 1987. Digestive Physiology.

Chapter 3 in Rabbit Feeding and Nutrition. Orlando: Academic Press

Fraga, M. 1990. Effect of type of fibre on the rate of passage and on the contribution of soft feces to nutrient intake of finishing rabbits. Journal of Animal Science 69:1566-74.

Gidenne, T. 1992. Effect of fibre level, particle size and adaptation period on digestibility and rate of passage as measured at the ileum and in the faeces in the adult rabbit. British Journal of Nutrition. 67:133-146.

Sakaguchi, E. 1990. Digesta retention and fibre digestion in brushtail possums, ringtail pos sums and rabbits. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology 96A:351-54.

_________. 1992. Fibre digestion and digesta retention from different physical forms of the feed in the rabbit. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology 102A, no. 3: 559-63.

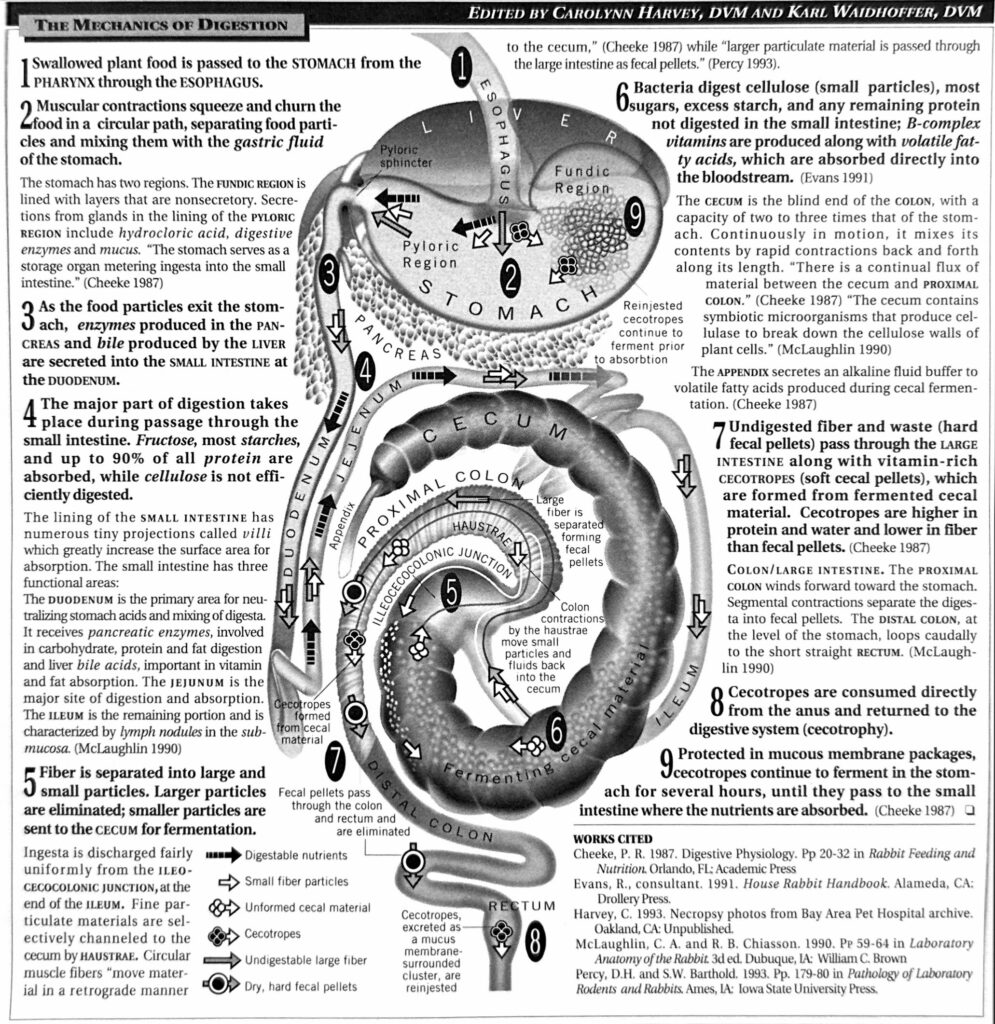

The Mechanics of Digestion

Diagram by Bob Harriman/Drollery Press.

Edited by Carolynn Harvey, DVM and Karl Waidhoffer, DVM DVM

Digestibility in the Rabbit Diet was originally published in House Rabbit Journal v3n3.

©Copyright Marinell Harriman, Dr. Carolynn Harvey DVM. All Rights Reserved. Republished with the permission of the author.